Equine ReproductionEmbryo RecoveryEmbryo Transfer |

|

Equine Reproduction SVC |

|

ERS is the longest, continually in existence Equine Embryo Transfer Company in the United States |

|

817 946 5132 |

|

Foal Pneumonia Discussion “Rhodococcus equi”

Background

Rhodococcus equi is a common pathogen in foals between the ages of 1 and 6 months and is most infamous for its ability to cause pneumonia. Classic R. equi infection results in the formation of large abscesses throughout the lungs of young foals, which can be especially difficult to treat because the bacteria are able to hide from the body’s immune system by living within white blood cells. The primary source of infection may also arise from the alimentary tract. R equi frequently colonizes the gastrointestinal tract of horses.

R equi is a facultative, intracellular, nonmotile, non–spore-forming, gram-positive coccobacillus (an organism that has the ability to exist as a coccus or bacillus or intermediate form). Electron microscopy of R equi in equine macrophages demonstrates that the organisms appear to avoid being killed by interfering with phagosome-lysosome fusion. Called Rhodococcus because of its ability to form a red (salmon-colored) pigment and is currently grouped with the aerobic actinomycetes. Of the 40 genera in the actinomycetes group, the Rhodococcus genus is placed among the nocardioform bacteria, along with the genera Mycobacterium, Nocardia, Gordonia, Tsukamurella, and Corynebacterium.

In addition, R. equi can cause septic arthritis. It can also cause sudden death in foals that appear to be healthy. R. equi is a ubiquitous gram-positive bacterium that lives in the soil and feces of herbivores. In North America, pneumonia caused by R. equi tends to occur only sporadically except on some farms where pneumonia caused by R. equi is endemic. On farms where R. equi is endemic, approximately 10-28% of foals develop clinical signs of pneumonia. In moist environments, R. equi can live in the soil for approximately one year.

Foals become infected when they ingest or breathe in the bacteria in soil, dust, and fecal particles. The bacteria then multiply inside macrophages eventually destroying them. While most foals are exposed to R. equi at some point, not all foals develop disease. It is likely that a combination of the foal’s immune status, environmental factors, and farm management practices all play a role.

R. equi is a particular problematic bacterium in the equine industry because of its high prevalence and mortality rate, associated economic losses to the breeding industry, and potential negative impact on future athletic performance of foals that recover.

R equi was first isolated in 1923 from foals and previously was known as Corynebacterium equi.

Clinical Findings

It is currently hypothesized that foals become infected with R. equi before two weeks of age; however, clinical signs of infection are not obvious until the foal is 30 to 90 days old.

Early clinical signs include, coughing especially during eating or exercise, respiratory rate above 30 breaths per minute, intermittent fever, an increased respiratory effort (using an abdominal press to assist breathing), depression or failure to nurse/eat, growth retardation, and at times mucopurulent nasal discharge. Later in disease, wheezes or crackles are present with thoracic auscultation. Labored breathing and cyanosis can occur in the most severe cases with extensive pulmonary involvement. Lymph node enlargement may be noted. The intestinal form of the disease may manifest itself by fever, depression, anorexia, weight loss, colic or diarrhea. Foals with immune-mediated polysynovitis will present with multiple joint distension accompanied by mild or no apparent lameness. Heat, pain and severe lameness are characteristics of R. equi septic arthritis or osteomyelitis. |

|

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of R. equi pneumonia in foals is challenging, particularly during the early stages of the disease. Diagnosis is based on clinical signs and physical examination. A positive diagnosis of R. equi is achieved in young foals with clinical signs consistent with R. equi that have evidence of pulmonary abscesses on radiographs and ultrasound and a positive R. equi culture from a sample obtained by a transtracheal aspirate. A complete blood count (CBC) may reveal neutrophilic leucocytosis, hyperfibrinogenemia (high fibrinogen level), and high white blood cell count. The CBC can be used to monitor the response to treatment. A DNA test for R. equi is available but has not been widely used.

In contrast to other infections R. equi presents diffuse abscess formation on thoracic radiographs compared with ventral opacification with alveolarization or consolidation in foals with Streptococcus zooepidemicus pneumonia.

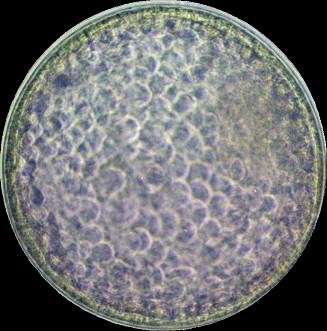

Thoracic ultrasonography may reveal comet tails and/or cavitary lesions ventrally in foals with Streptococcus pneumonia and extensive diffuse cavitary lesions in foals with Rhodococcus. Ultrasound is less sensitive when the surface of the lung is normal; however this occurs in but a few cases.

Treatment

Foals diagnosed with R. equi are prescribed a variety of antibiotics, with the most effective being a combination of erythromycin estolate and rifampin. This combination of antibiotics allows the drugs to penetrate the lung abscesses and the macrophages where the bacteria are multiplying (these “walled off” abscesses are the reason more common antibiotics are ineffective). Treatment should continue for at least 3 weeks after diagnostic parameters become normal. Prolonged treatment of six to eight weeks or longer is not unusual. Fibrinogen levels, white blood cell counts and radiographs are used to help determine when to stop treatment. Antibiotic-associated side effects (because of the erythromycin) include hyperthermia (they get hot) and sometimes a mild diarrhea. The foal should be kept indoors as a foal receiving erythromycin therapy is light sensitive and the side effects are exaggerated occasionally causing death.

Prevention

Good farm management and sanitation strategies can help minimize infection. Mares and foals can be kept on grassy pastures rather than dry, dusty paddocks. Frequent removal of feces to minimize bacteria helps. A veterinarian should see any foal with clinical signs of respiratory disease. Lazy, unthrifty foals with a dull hair coat and using an abdominal press to breathe are in advanced stages of the disease.

No vaccine is available against R. equi. R equi hyperimmune plasma that contains high levels of antibodies (immunoglobulins) against R. equi is believed to help and is routinely administered on some farms. Evidence shows the plasma provides a passive immunity to treated foals against R. equi administered shortly after birth and reduces the incidence of pneumonia caused by this bacterium. The plasma is repeated at 3-4 weeks of age.

Several broodmare owners are electing ultrasound screening of their valuable foals at 2-3 week intervals to potential apprehend R. equi in the early stages on the disease. Several veterinary practices in the Weatherford, Texas and elsewhere offer this service. |